Writing the dead: remembrance and the written word

Writing about the dead is a compelling way to remember. Capturing a person’s character, their likes and dislikes, their stories and memories on paper – or online – feels like a good way to remember them as an individual. This can take so many forms, from a notice or obituary in a newspaper to a full-length biography, from a Facebook post on the anniversary of their death or birth to a few pages about their life circulated around a family and friends. And this form of remembrance has become compelling during the Covid-19 pandemic. Faced with our own mortality and that of our older relatives perhaps more starkly than ever, many of us have turned to writing and recording memories: the Guardian, for example, described a huge surge in the demand for ghost-written memoirs of family members, and particularly elderly parents. Others have turned to self-publishing memoirs or biographies, an option making publishing in some form increasingly accessible. This parallels movements in oral history, too, to record the memories of the elderly and dying whilst it’s possible – such as a project in Sheffield which records interviews with hospice residents.

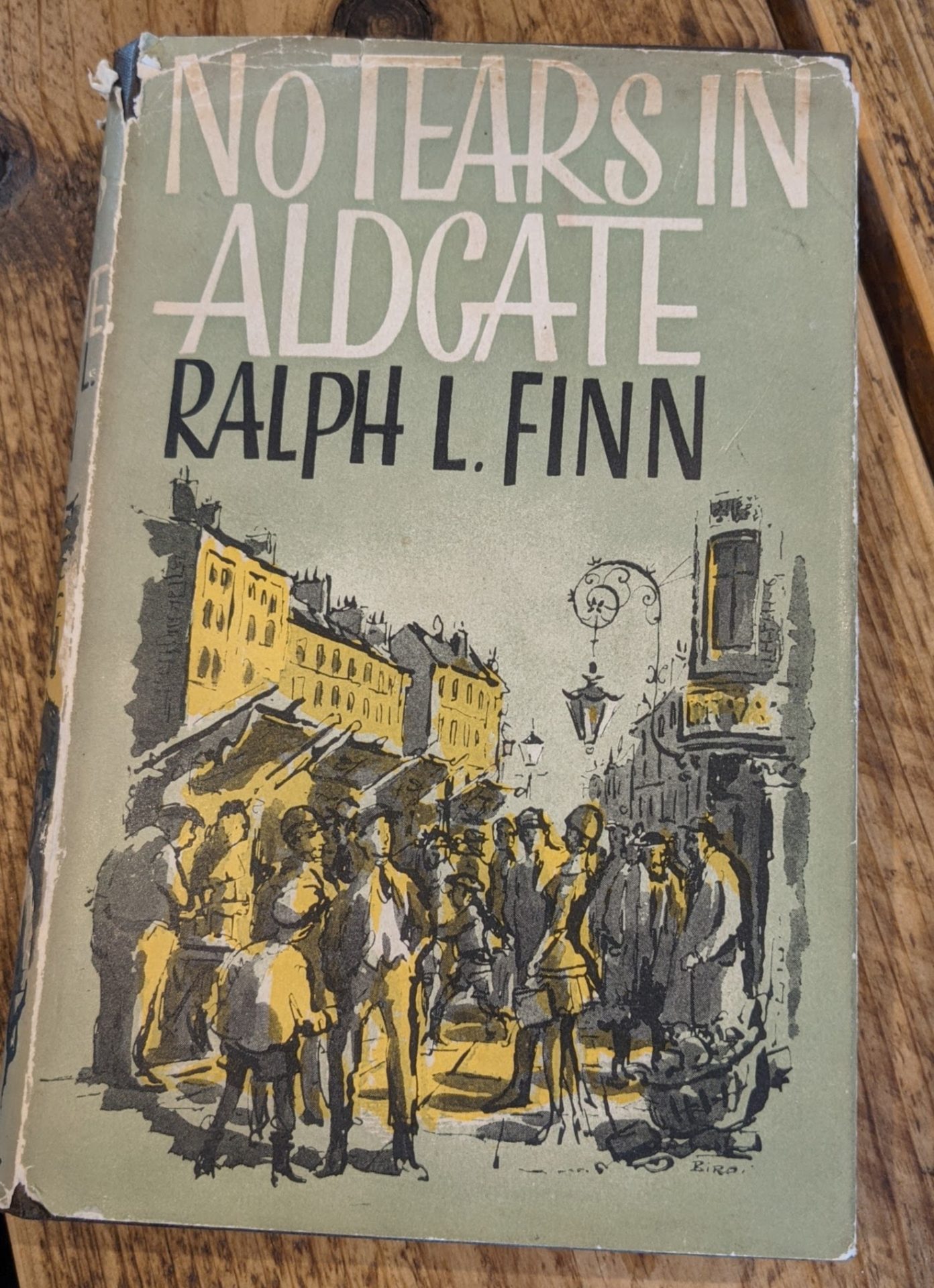

But this trend goes much further back. And with the boom of publishing of ‘ordinary’ people’s writing throughout the twentieth century in Britain, as the words of working-class people, women, people of colour and many others became increasingly valued, there was more (published) space to use the written word to pay tribute to relatives now gone. Ralph Finn, for example, born 1912, started his first autobiographical book, No Tears in Aldgate, with a foreword on why he wanted to write. He discussed the ‘truth’ of the contents of the book: ‘Everyone in this book existed. No, exists. For me they can never die.’ Both this book and his follow up, Spring in Aldgate, later published as Grief Forgotten, are works written with the explicit desire to commemorate the lives of relatives and friends of Ralph’s who had died. Spring in Aldgate begins with a similar thought, that though most of those he writes of are dead, ‘the aliveness of their spirit is indestructible’. Throughout his writing is a sense of paying tribute to and recording the place, community, way of life and experiences of the Jewish East End. Like much autobiographical writing, there is within it a strand of loss, for a time and place now gone. For Ralph, writing the lives of his family members and friends was a form of remembrance, a way of keeping those he had lost alive.

But this trend goes much further back. And with the boom of publishing of ‘ordinary’ people’s writing throughout the twentieth century in Britain, as the words of working-class people, women, people of colour and many others became increasingly valued, there was more (published) space to use the written word to pay tribute to relatives now gone. Ralph Finn, for example, born 1912, started his first autobiographical book, No Tears in Aldgate, with a foreword on why he wanted to write. He discussed the ‘truth’ of the contents of the book: ‘Everyone in this book existed. No, exists. For me they can never die.’ Both this book and his follow up, Spring in Aldgate, later published as Grief Forgotten, are works written with the explicit desire to commemorate the lives of relatives and friends of Ralph’s who had died. Spring in Aldgate begins with a similar thought, that though most of those he writes of are dead, ‘the aliveness of their spirit is indestructible’. Throughout his writing is a sense of paying tribute to and recording the place, community, way of life and experiences of the Jewish East End. Like much autobiographical writing, there is within it a strand of loss, for a time and place now gone. For Ralph, writing the lives of his family members and friends was a form of remembrance, a way of keeping those he had lost alive.

In his writing of the dead, Ralph rejected a notion of death as about the biological body, suggesting instead that as long as they are remembered, the dead remain in a very real sense alive. In his final two sentences in No Tears in Aldgate, short of an endnote about the family leaving his childhood home, Ralph embraced this sense of confusion and emphasised a spiritualist sense of sitting comfortably with the dead: ‘Ah youth, lost and windborne. Ah the friends, the family, the dear ones, the departed. Ah those voices from the dead past. Come again, lost ones, forever lost, forever living. Come and haunt me now and through eternity.’ In Ralph’s writing, the presence of his deceased loved ones was an embodied and emotional experience. Such writing has been seen as nostalgic and sentimental. Perhaps it is. But that doesn’t matter. In his emotional exploration of his own and his family’s past, Ralph shows how relationships with the dead, those ‘continuing bonds’, remained important, and how writing provided a way to inhabit and make visible these relationships.

The writing of the dead could be important – keeping hold of handwritten letters, greetings cards, or other forms of writing, for example, was and is popular, and became particularly important during both world wars. But writing about and for the dead too has been long a comforting form of ‘keeping alive’ loved ones. One thing I’ve been struck by in this research project is the vast number of published and unpublished books, pamphlets and collections of pages, handwritten and typed, held across the country in so many archives and libraries. Some are profiles of relatives, written with the express aim of telling a reader about that deceased person. Others are autobiographical pieces, like Ralph’s, but contain memories and explicit tributes to relatives now deceased. Still other books and pamphlets might be family histories, a collection of information about a number of different relatives, and often other friends and acquaintances too. Yet, diverse in their forms, all act as a means of remembrance and show a desire to ‘keep alive’ those now gone. Depositing that information somewhere public is a way of giving an afterlife to those no longer here.