The Woman Who Changed the Face of Death

This week’s post turns our attention to a pioneer in changing medical treatment for the dying, Cicely Saunders, in Ruby's contribution to our series of blog posts from MA students.

By Ruby Lucas, MA Student, University of Leeds

As the rather dramatic title of her biography, ‘Changing the Face of Death’ suggests, Dame Cicely Saunders’ incredible contributions to end-of-life care are not something to be understated. A 6-foot-tall powerful and commanding woman, Saunders used her unconventional background in nursing, social work and eventually medicine, to pioneer the modern hospice movement, establishing St Christopher’s Hospice in 1967. She is widely respected amongst those that have heard of her story, and there were even petitions to put her on the most recent £50 note!

It is hard to believe that before 1967, the majority of patients suffering with chronic terminal illnesses would have passed away in a crowded hospital ward, or at home without any medically-managed pain relief. St Christopher’s changed this, paving the way for a new way of treating people at the end of their lives.

With Britain’s ageing population on the rise, now more than ever we must consider what makes a ‘good death’. Saunders’ letter to the BMJ offers insight into the foundations of her revolutionary philosophy, helping us to answer this complicated question.

Cicely’s letter

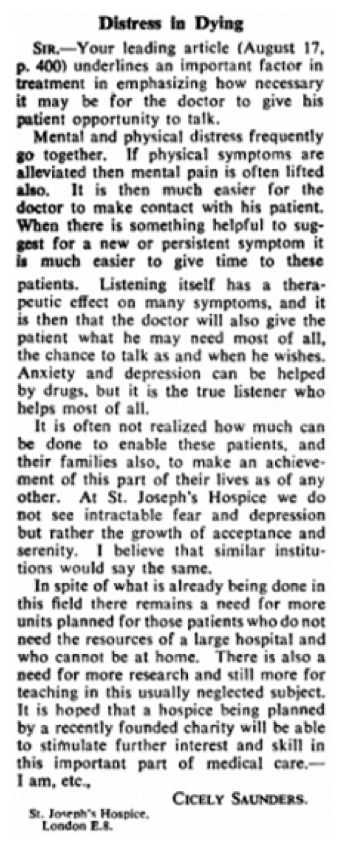

Cicely’s unique and ground-breaking approach can be exemplified in the letter pictured below. Published in the correspondence section of the British Medical Journal’s (BMJ) September 1963 issue, the letter was a reply to the initial article printed the month earlier, entitled ‘Distress in Dying’ which highlighted the reality of the mental distress patients were experiencing in their ‘final hours’.

The rights to use this image have been accepted for academic reuse, 1963, requested accessed from: https://www.bmj.com/content/2/5359/746.2

This was the first time Saunders had appeared in the BMJ and was a significant achievement - to be published in such a highly-regarded journal indicates that her ideas were already beginning to gain traction, and marked the start of a lifetime of being published in such journals.

The letter itself is extremely useful as it outlines all of the key principles of Saunders’ unique philosophy: compassionate care, alleviation of ‘Total Pain’ and a humanizing approach. Cicely’s compassionate nature is instantly striking as she emphasizes the importance of ‘giving the patient [an] opportunity to talk’, counteracting doctors’ typically detached bedside manner. Saunders was known to establish deep emotional connections with her patients, having even fallen in love with patient David Tasma, who was said to have been the inspiration for St Christopher’s.

Saunders understood how much psychological support patients needed. She felt that the NHS’ purely biological, disease-based approach was insufficient and instead campaigned tirelessly for a holistic management of care for the dying. Her pioneering concept of ‘Total Pain’ was levelled at tending to a patient’s physical, as well as emotional, psychological and spiritual well-being. Saunders’ belief in the indivisibility of mental and physical pain is encapsulated in a line in the letter: ‘If physical symptoms are alleviated then mental pain is often lifted also’ – and was the key principle behind St Christopher’s humanizing and attentive approach.

Medicalization debate

Hospices have often been cited as an example of how death and dying have been medicalized in today’s society - how everyday human social problems have come to be defined and treated in medical terms. Sociologist Ivan Illich argued that hospice care was a prime example of how the scope of modern medicine has extended beyond what it ought to, arguing hospices ended the era of the ‘natural death’. Before the formation of the NHS in 1948, Pat Jalland explains that almost all people, including those with terminal illnesses, passed away in their home, surrounded by family. However following the introduction of the National Health Service, it became the norm to die in hospitals or medical institutions – today only 20% of patients in the UK die at home. Hospices were said to exemplify the over-medicalization of dying because integral family rituals of death and grieving were replaced by the more clinical, professional approach to death.

However, this interpretation overlooks Cicely’s original intentions for hospice care, as her vision was a far cry from a traditional clinical environment. Her letter to the BMJ can help weigh in on this debate as the fundamental values that she discusses show that her template for compassionate, holistic, patient-centered hospice care represented a move away from the cold, clinical medicalization of care for the dying.

The letter also holds significance in that it was written before the opening of St Christopher’s hospice, unlike the majority of Saunders’ published writings, giving us an invaluable insight into the ideas that motivated her later work and plans for the hospice. In fact, the current CEO of St Christopher’s has stated that “[we] still look to her writing ... as a way of thinking about our care for the future”, demonstrating the continued relevance of her early writings to this day.

Wider significance

Cicely’s work had a wider effect on the culture of death. Her idea that care for the dying was important and necessary was popularised by the quote:

‘You matter because you are you, and you matter to the end of your life’,

an idea that she also reiterated in her letter: ‘[it is important to] make an achievement of this part of their lives as of any other’. Saunders also passionately challenged the perception of death as a failure in the medical system. As an inevitable part of every person’s life, she argued the health service ought to provide compassionate palliative care and, as Dr Atul Gawande echoes, teaching on death in medical school. She also challenged society’s general reluctance to talk about death - by writing such open letters about end-of-life issues, she set a precedent for breaking the ‘final taboo’.

Nowadays, the issue is more prevalent than ever. As quality of life improves, life expectancy in Britain is also increasing, putting more pressure on end-of-life services. Sources like Saunders’ letter prove valuable as we are able to remind ourselves of the core values that inspired the hospice movement - the story of how one woman’s compassion and conviction brought about lasting and revolutionary change to people in their final days.

Further readings

Du Boulay, Shirley, Changing The Face Of Death (Norwich: Religious Education Press, 2001)

Clark, David, "Between Hope And Acceptance: The Medicalization Of Dying", BMJ, 324 (2002)

Gawande, Atul, Being Mortal (London: Profile Books Ltd, 2015)

Lawton, Julia, The Dying Process (Hoboken: Taylor and Francis, 2002)