Exploring Counter Memorials: The UK AIDS Memorial Quilt

Our series of blog posts from MA students continues to focus on the material culture of remembrance with a post from Jessica, on AIDS memorial quilts.

By Jessica Heath, MA Student, University of Leeds

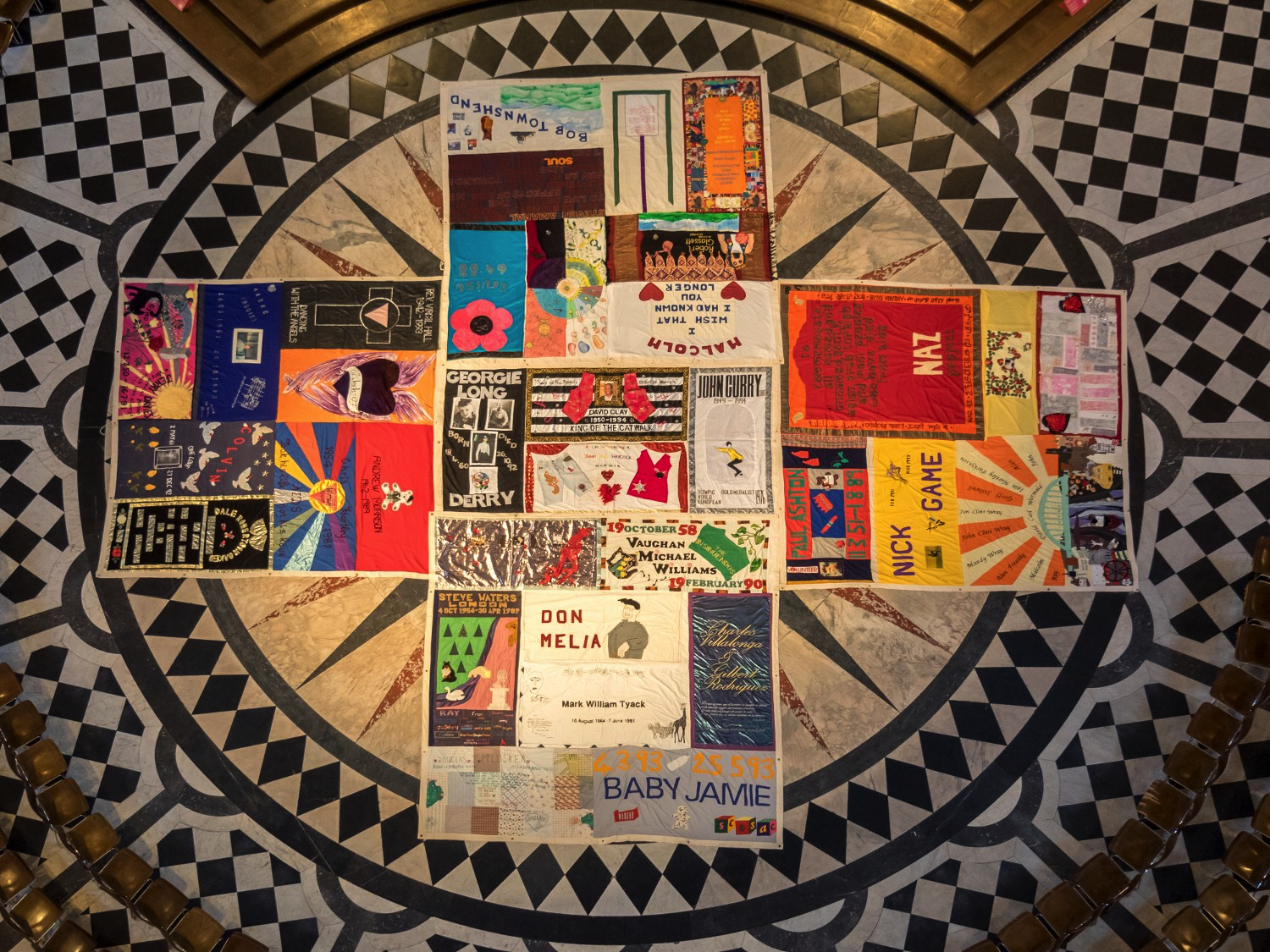

The AIDS quilt at St Paul's Cathedral (from http://www.aidsquiltuk.org/st-pauls-cathedral/)

The UK AIDS Memorial Quilt was produced to memorialise those who lost their lives during the 1980s HIV/AIDS crisis. The AIDS Memorial Quilt Conservation Partnership was created to raise awareness of the quilt and to conserve it for future generations.The custodians of the quilt, the George House Trust, require a week to set out all 430 m2of material. It is made up of 48 panels each consisting of 8 individual dedications. As such the quilt serves as a memorial to those who died and an embodiment of the grieving process their loved ones experienced.

From 1981 to 1994, 11,516 people were diagnosed with AIDS and 8,901 died. The crisis enfolded against a backdrop of stigma and fear about HIV, and homophobia towards the LGBT+ community. In 1986 the British Government launched "AIDS: Don't Die of Ignorance", a public information campaign warning it was impossible to tell who was infected with the virus.Margaret Thatcher’s government passed Clause 28 of the Local Government Act, in 1989, forbidding public bodies such as schools from ‘promoting’ homosexuality as a ‘pretended’ family unit.

The death of LGBT+ activist Mark Ashton, who is memorialised in the quilt, was remembered by a friend because of the heartless response from her colleagues. When the friend was overheard telling her boyfriend Mark had died from AIDs, the following day her desk had been moved to the far side of the room and her colleagues refused to speak to her. One man told her he couldn’t risk contact with her as he had children. Newspaper reports from the time, similarly added to the culture of shame and stigma helping to silence individuals’ grief. For example, The Daily Mail’s reporting of actor Rock Hudson’s death in 1985 with the headline that Hudson had ‘died a living skeleton – and so ashamed’.

The impulse for many who lost people to the disease was secrecy. Describing the funeral of his friend Bruno, the author Simon Watney describes how Bruno’s parents felt ‘condemned to silence’. Watney lamented the stark juxtaposition between the silent shame that adorned his funeral and the Bruno whom Watney had known as ‘magnificently affirmative and life-enhancing’. This, he wrote, ‘was all but unbearable’. The stigma surrounding HIV/AIDS meant there was no national, formal recognition or commemoration of the crisis.

The UK quilt was inspired by an American quilt, started by activist Cleve Jones in response to the AIDS death toll in San Francisco reaching 1000 in November 1985. At the San Francisco Candlelight Parade marchers were asked to write the names of deceased on pieces of cardboard, to be taped onto the wall of the San Francisco Federal Building, as it occurred to Jones if many corpses littered a field the public impact would be more substantial. In June 1986, Jones and his friends made a quilt in memory of their friend Marvin Feldman. This led to the launch of the NAMES Project and by October 1987 the quilt was put on public display, with 1,920 panels, for the first time on the National Mall, Washington D.C.

Jenifer Power argues the American project drew on traditions of quilting as folk art and of passing them onto subsequent generations; harnessing a nostalgia for nineteenth-century rural community. Further, Cleve Jones said ‘we picked a feminine art’, ‘to try and get people to look beyond an ‘aggressive, male sexuality component’ so often associated with the AIDS crisis. Inspired by the quilt making in the US, the NAMES project UK was started with the first panels being produced in 1988. It serves to remember the dead by sewing together fragments of their lives for public display. Research by Christopher Breward shows that craft-production was acknowledged as a healing tool in nineteenth-century military and medical circles. Thus, the quilt continues these mourning tradition as well as being ‘collectively… part of the largest piece of community art in the world’ according to artist Grayson Perry.

Personal objects such as wedding rings and badges were sewn onto the panel and photographs, letters and personal documents were included in an accompanying folder. Vaughan Williams’ panel was accompanied by a letter detailing those who created it. One of Vaughan’s friends, Dr Gill Brigg, commented on the displaying of the quilt at St Paul’s Cathedral: ‘Vaughan would be very proud’- demonstrating the solace found from deceased how loved ones would have perceived the gesture.

Margaret Gibson’s work looks at the importance of personal objects to mourners, particularly items that have touched the body.Early drafts of Scott MacDonald’s panel contained his cigarettes and nursing badges. Gibson notes that such objects are often held as ‘sacred’, yet are sacrificed, as Power suggests, so others can connect with that individual.

The victims of the crisis were largely young men, drawing links to the casualties of both world wars, such as in the First World War. This tradition was continued with the Vietnam Veterans memorial proposed by Maya Lin in 1980 – 140 panels with 58,000 names. The quilt continues a military tradition of mourning. However, it differs because the UK quilt often uses more intimate nicknames or first names. This Hawkins argues signals ‘a cherished intimacy’, or considering attitudes to AIDS, a ‘withholding an identity’ that a surname would give away – protecting a family from exposure.

However, unlike war memorials the quilt acted as a ‘counter-memorial’ a term used to describe memorials that attempt to challenge mainstream public attitudes. It also worked to contest stigmatic imagery and views cast upon AIDS victims. The act of memorialising someone who died is a declaration that the individual deserves to be remembered, celebrated and is ‘grievable’. It asserts that people who died from AIDS were worthy of public commemoration. The quilt gave people an opportunity to grieve collectively and publicly, functioning as a ritual of remembrance and helping with grieving processes.

There is a duality in the quilt. It acts as a whole commemorating all that died from HIV, not just those on the quilt, and it is individual with personal stories of those it immortalises. As a piece of public art, that is still viewed, the quilt humanises those who died through the personalisation and naming process of each panel. As a process of creation it allowed mourners to engage in a task to harness their emotions into something physical and aid with the grieving process. It also helped bring individuals together in a collective state of mourning and gave them a tactile object that almost contains the lives of those they lost.