A Personality Preserved by Poetry

Continuing our series of posts from students on module entitled ‘Death, Dying and the Dead in Twentieth-Century Britain’, Susy writes about her own family history, and a poem she thinks captures the memory of her grandfather and his brother.

By Susy Goldstone, MA Student, University of Leeds

I was not fortunate enough to meet my paternal grandpa, Maurice Goldstone. He was born in 1923 in North Manchester, not too far from where he died in 1992. He was the second of four siblings born to Simon and Bertha Goldstone, who themselves were the first of their families born in Britain, their parents having emigrated from Russia in the late nineteenth century as did many Jewish families of that time.

Maurice Goldstone, 1943

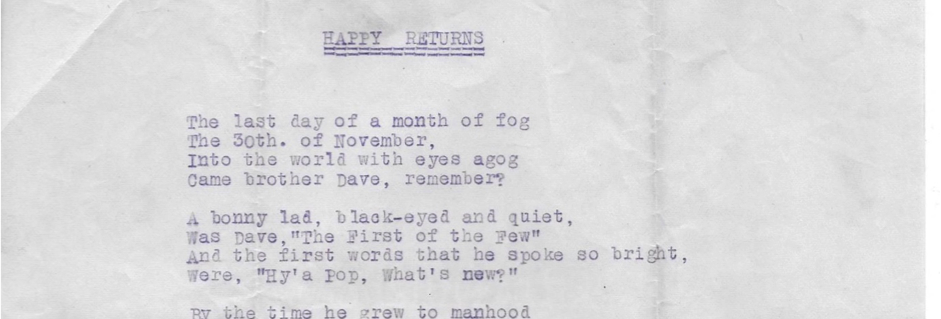

Maurice and his elder brother David shared a close relationship. Even after Maurice’s death, David remained close to my family until his death in 2015. However, it was only recently that I stumbled across an item that really showed the connection between the two brothers as well as Maurice’s personality. My dad had a small collection of photos, mainly of Maurice and my grandma, that he asked me to scan into the computer in order to back them up. However, hidden amongst these photos was a poem, typed on an A4 sheet of paper from 1943. My dad didn’t think much of it, after all it was just something his father had written a long time ago that had been kept within this collection of photos. However, I saw it as something more significant than that.

The poem, entitled ‘Happy Returns’, was written in 1943 by Maurice Goldstone on the occasion of David’s twenty-second birthday. In 1943, the brothers were stationed abroad due to the Second World War – Maurice in North Africa with the Army, and David in India as a mechanic for the Air Force. The poem is a comedy about David’s life, including information about his birth (at which Maurice was clearly not present) and his military service. However, the poem also has the effect of presenting Maurice’s characterful, joking personality as well as his relationship with his brother. The comedic aspects of ‘Happy Returns’ preserve Maurice’s individuality, arguably immortalising him. Without having to be told anything about Maurice’s life, his creative expression enables me to remember him as he was.

However, this approach does have limitations. Firstly, there is no way of confirming that the poem does in fact reflect Maurice’s personality without talking to those who knew him. Without that confirmation, the inferences made from his poem cannot be proven as fact. However, this was not the only poem that Maurice wrote during his lifetime. Also kept in my family (unaware to me at the time of first reading ‘Happy Returns’) are copies of more comedy poems he submitted to a newspaper, some of them dating as recent as 1986. Unlike ‘Happy Returns’, these poems, are comedies about Jewish characters and were therefore most likely published in the local Jewish newspaper – the Jewish Telegraph. The subject matters include a religious woman who can’t find a husband, a Jewish Native American, a Navy sailor named Finkle-steen, and a supernatural lulav(a plant that is used symbolically in the Jewish festival Sukkot). These poems further enhance Maurice’s personality, showing not only that he was continuing to write in his sixties, but also that he was involved in the local Jewish community – something which ‘Happy Returns’ doesn’t touch on.

The second limitation of using creative expression as a means of remembering the deceased is that someone might not necessarily have access to other works produced by that person. If I hadn’t found the later comedy poems, there would have been no evidence that my assumptions about Maurice’s personality were correct. Therefore, if this type of material was to be archived, it would be ideal to keep the different poems together so that they can be compared and used concurrently with each other. Additionally, it would be useful for other types of sources connected to the person to be kept similarly. For example, there is a newspaper clipping of an article about Maurice’s involvement in the Society of Inventors. The article gives us lots of information about Maurice’s life, namely his occupation, address, and the fact that he was the secretary of the Society – indicating the depth of his enthusiasm in inventing. This article particularly focuses on three of his inventions – a netting suspended by gas balloons to keep birds off crops, an onion peeler assister to prevent streaming eyes during onion preparation, and a steel rod fire escape. This information adds a great deal to his personality, showing that he was creative in inventing as well as poetry. Using ‘Happy Returns’, the Jewish comedy poems and this newspaper article alongside each other paints a clear picture of Maurice as a funny, creative, witty person, therefore preserving his memory.

Historians have, on the whole, yet to fully delve into this topic. However, there is a general consensus that a piece of creative work can preserve a person’s identity and personality. Robert Ellrodt, in his study of poetry, argues that ‘the author does speak and, when the writing is not purely imitative, does reveal some characteristics of his identity.’ Similarly, Margaret Gibson in her article, ‘Melancholy Objects’, argues that objects a person has owned are also embedded in the construction of identity, and I would argue that personal creations such as poems are included within this category. I believe that Maurice’s ‘Happy Returns’ alongside the other sources mentioned could very easily be used within this field and enhance any further studies of it.

‘Happy Returns’ is a highly significant contribution to the study of how we remember the dead, as it emphasises the idea of looking at objects createdby a person as well as those collected and owned by them. In addition to contributing to the study of British soldiers in the Second World War, the poem shows how a person’s creative expression reflects their personality, preserves their identity, and ensures they are remembered even by those who didn’t know them personally. In short, looking at the material created by a person is another under-researched way of thinking about the dead and how we remember them.