Violet Dix: A Life Lived and A Death Displayed

As part of a module entitled ‘Death, Dying and the Dead in Twentieth-Century Britain’, some of my MA students have written blog posts about different aspects of death and dying in this period. I’ll be publishing these here fortnightly, and we start with Debra Kontowtt’s fascinating post about a special trunk, kept in memory of a little girl who died. This strong parallels work I’ve been doing in collaboration with family historian Maureen Jessop on the school case of ‘Poor Harold’– who died ten years later….

Violet Dix: A Life Lived and A Death Displayed: Post Mortem Photography in the Early Twentieth Century

By Debra Kontowtt, MA Student, University of Leeds

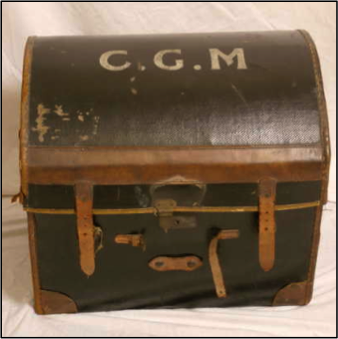

The trunk containing Violet's belongings

To show an image of a trunk may seem confusing when the topic under discussion is of post mortem photography. But in this trunk, amongst a treasure trove of a young girl's belongings, was also found a post mortem photograph. We can use these cherished possessions to understand how life was not only lived in a typical British town in the early twentieth century, but also to learn how people were remembered after their death.

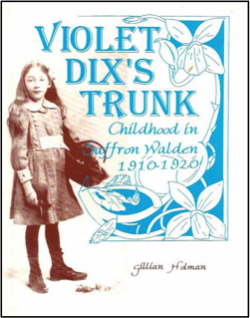

Violet Annie Dix was born in 1909 in Saffron Walden, and died aged 10 after having surgery for an inner ear infection in a London hospital in 1919. We know about Violet thanks to the leather trunk which was donated to Saffron Waldon Museumby Violet's niece Helen Rose, which has featured in exhibitions relating to social and local history in Saffron Walden. We also know about Violet because of a book by Gillian Holman based on the trunk, published in 1996.

Some of the contents of the trunk

The trunk contains many of Violet's belongings and although it's not certain who packed it, it was most probably Violet's parents after her death. Inside the trunk were many items which belonged to her: clothes, school books, letters, photographs and also items which relate to her death - letters of sympathy, in memoriam cards and the focus of this blog post - a photograph which shows Violet lying in her coffin, laid out before burial.

And post-mortem photography means exactly what the name suggests - it's the practice of photographing the recently deceased which was kept as a reminder of the certainty of death. In Violet's case her photograph was taken by a local photographer after her body was brought back to Saffron Walden for burial. In the photograph Violet appears to be sleeping and her pose reflects the standard pose which can be seen in twentieth-century post-mortem photographs: a white nightgown was usually worn, the arms of the deceased were folded across the chest and sometimes flowers were placed on the body. But these protocols contrast quite sharply with nineteenth-century photographic images of the recently deceased, in which quite often the dead person was photographed alongside living relatives. But by the early twentieth century it had become standard practice by photographers to play down the fact that they were dead and to photograph the deceased as if they were simply sleeping, such as in Violet's case.

Now this may sound quite outrageous to us today, but post-mortem photography was widely practised in America from around 1840, although in Victorian Britain it was quite scarce. Audrey Linkman has written widely on post-mortem photography, and argues that although she's seen hundreds of thousands of conventional portraits of the living, she's only seen approximately two to three hundred British post-mortem photographs. So why was this? Well anthropologist Jay Ruby has argued that post mortem photography was a very private affair and that we are only aware of the images because of what he calls

“…an accident of history” (Jay Ruby, 1995)

as the photographs only survive because a descendent decided to sell an item or donate it to a museum, with the photographs being found inside - exactly what happened in Violet's case.

And by the mid-twentieth century people became reluctant to employ professional photographers which was a challenge when it came to finding an example from the twentieth century - there were many from the Victorian era and quite a few from the early twenty-first century, but nothing in between. However, since the end of the twentieth century there's been a shift towards it becoming more prevalent in hospital bereavement careparticularly in perinatal deaths, with medical photographers specially trained to act under certain guidelines to help them carry out their task as discreetly as possible. And charities such as Remember My Babynow aim to offer post mortem, or as they more sensitively call it, remembrance photography, to all UK parents who experience the loss of their baby.

So why take a picture of someone, especially a young child, at their death? Well far from being macabre, historians have suggested that post-mortem photographs were viewed as tokens of love and affection which capture the serenity of death. And it's been argued that taking a photograph of a deceased loved one can assist with the process of coming to terms with the loss whilst helping parents accept the reality of their child's death.

And what can we learn from both the post-mortem photograph of Violet and also the rich information provided by the trunk which show its significance and value as a source?

- it was thought that in the early twentieth century post mortem photographs were often the only time that someone may actually have been photographed, what's significant here is that in Violet's case this wasn't so - there were many photographs of her found in the trunk.

- we can learn of the frailty of life in the early twentieth century. Infections which are now cured by antibiotics were often lethal, requiring a dangerous operation such as in Violet's case, leading to her untimely death.

- whilst some believed that post-mortem photography was a morbid nineteenth century custom this source shows something quite different, that these photographs were treasured as a loving remembrance of the departed.

- the end of the First World War marked a shift in attitudes towards death from the outward expressions of grief shown in the Victorian era to ones of keeping that grief hidden and locked away. Violet's trunk represents a society on the cusp of this change.

But whatever the private motivations were behind post-mortem photography, Violet's photograph shows death as being a serene and peaceful sleep, intended to ease the pain of loss and to bring comfort and solace to the bereaved. Sleep peacefully Violet.

Images

The image of the trunk and its contents are courtesy of Saffron Walden Museum.

The image of Gillian Holman's book is courtesy of Ian Henry Publications Ltd.