Reflecting on Remembrance

‘Your generosity can change lives’, promises the Red Cross, as its website suggests the reader ‘Leave a gift in your will’. Up until last week, I hadn’t realised how important legacy giving was to charities. Cancer Research UK, for example, relies on legacies for about a third of its income. The health related charities do well out of this kind of giving, but search for information about leaving money to charities in your will, and you can find invitations from Battersea Dogs Homeand Mencaptoo. Added to this is a growing emphasis on ‘in memory’ giving, such as the trend of asking mourners to give money to charity in lieu of buying flowers for a funeral.

Last week, I was invited by the Institute for Fundraising’s Legacy and In Memory Special Interest Groupto give a talk about my research and the exhibition on Remembrance we’ve put on over the last year. It offered a really useful chance to reflect on what the exhibition had offered visitors, and how they had reacted to it. It was also fascinating to meet charity fundraisers, keen to find creative ways to encourage charity giving in response to a death.

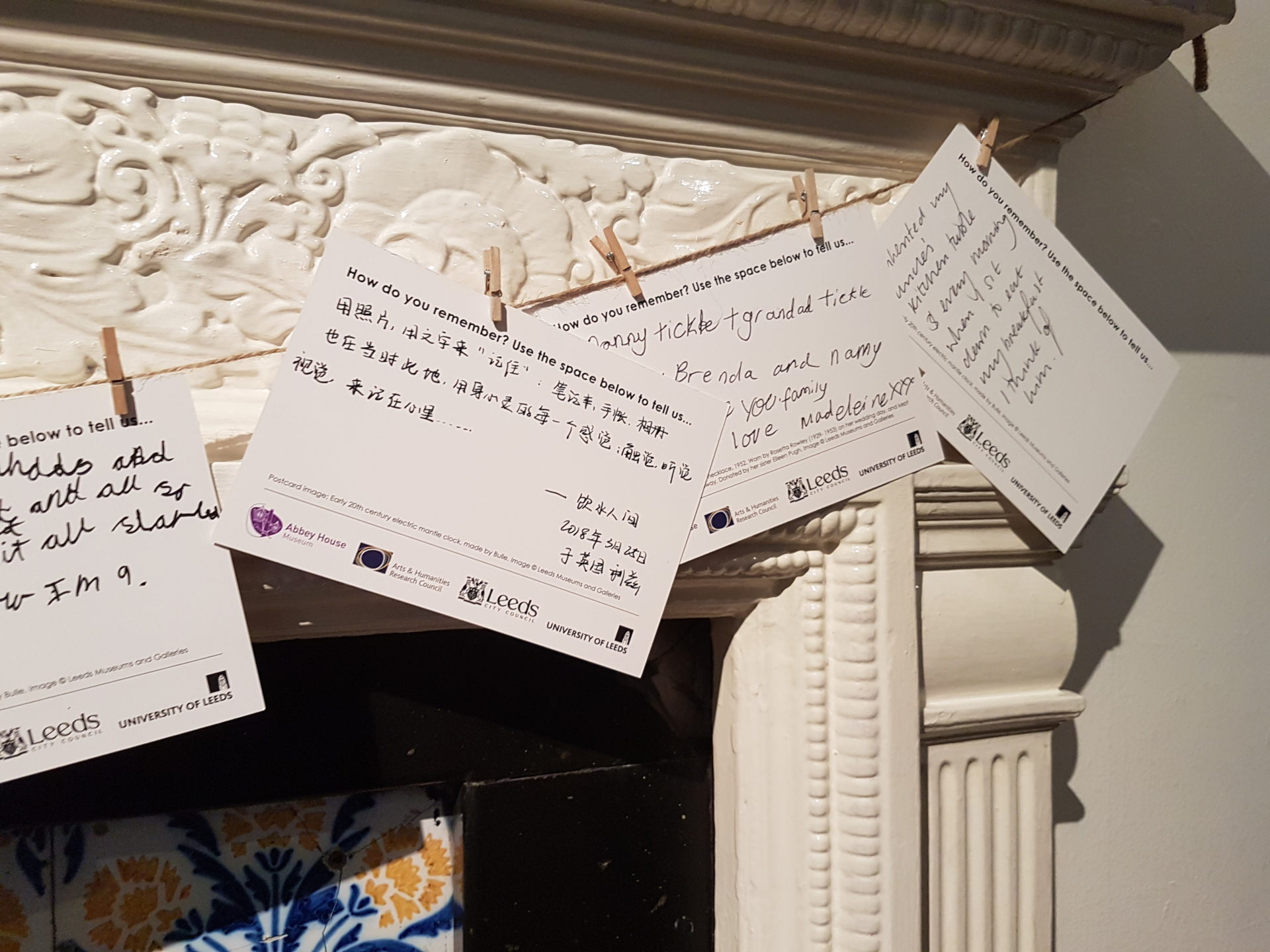

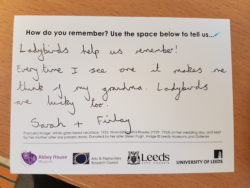

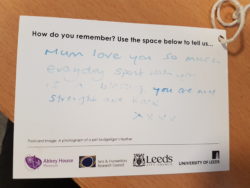

In my talk, I reviewed the feedback from visitors to the exhibition. As part of the exhibition we invited people to write in a book of remembrance, to answer the question ‘How do you remember?’ on a postcard, and send in a photo of a place that reminded them of someone they’d lost. The postcards in particular were a real hit, with an unprecendented number of people filling them in.

People used the postcards to record the lives of people important to them. Whether a grandparent, a pet, a child or a friend, the lives of hundreds of people and the special ways in which the writer uses to remember them have been recorded. One of the most striking consistencies across the postcards is how little detail there is of the deaths of the deceased – the details recorded are of their lives, their likes and dislikes, their eccentricities, and their habits. From favourite pieces of music to well worn phrases, the characters of the deceased are very much brought to life in the postcards. The ways in which people remember are very diverse and personal, but common themes of remembrance included music, food, learnt skills (like gardening or baking), as well as flowers and animals. Music, food and skills were a clear link to remembering doing things with the person who had died; flowers and animals seemed a more interesting link, whereby the sight of a ladybird or a freesia would call back that person’s memory.

Many visitors also used the postcards to write directly to the person they wanted to remember, such as a touching letter to a mother in which the writer describes how ‘every day spent with you was a blessing’. It’s striking, and touching, that the exhibition seemed to provide a space to feel close to or for people to want to reach out to those they had lost. Children were well represented here, with many postcards written by young children to or about lost loved ones, often grandparents or pets. Lots of people added smiley faces, kisses, hearts and drawings to decorate their postcards.

This tells us how personal and individual remembrance practices can be, and shows as much about the person doing the remembering as the remembered. It demonstrates the clear desire of people to continue to speak to or communicate with the dead after they’ve gone (which strongly ties to theories of continuing bonds, one of the most prominent ways of thinking about grief and bereavement at the moment). It shows how parents are keen to support their children remembering and communicating with those who have died – some children wrote about grandparents and relatives they had never met. And it shows how people are keen to remember the unique qualities and personality of the person who has died.

This was something of real interest to the charity workers I met. Legacy and in memory giving is often thought to be the preserve of charities which care for people in dying – hospices, charities like Cancer Research which seek to prevent disease, Macmillan nurses. But in fact, people want to remember life, not death, and there is a lot of potential here for charities reflecting the things people love, from animals to music.

There’s something a bit uncomfortable when thinking about how to ‘make money’ out of death, particularly given there’s often a perception that both money and death are a bit taboo in British culture. But there’s something that’s generous and perhaps even joyful here too, with the idea of planning out a really good use for some money after you die, or giving a bit of cash in remembrance of a loved one’s favourite hobby or political cause.

Apparently only 6% of people do leave a legacy in their will. Maybe more of us should be thinking about it?

There’s more information hereabout making wills and including a gift for charity, and raising money in remembrance. Is it something you’d consider?