A Museum of Memories: Sharing grief stories on the Journey with Absent Friends

Jessica Hammett, University of Leeds

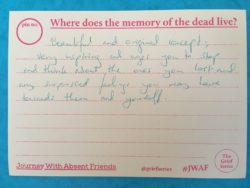

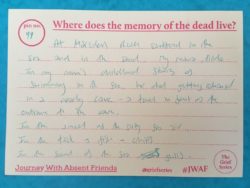

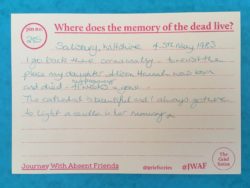

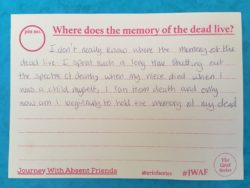

It's been just over a month since we got back from the Journey with Absent Friends – a month long pilgrimage with Perle the caravan, between sites of personal significance for artist Ellie Harrison – and we have been reading through the beautiful and moving stories that some of our visitors shared with us. There were a couple of ways people could do this inside the caravan: by filling in a card which asked 'Where does the memory of the dead live?' and putting a pin in one of the large maps to mark the location of the story; by recording their stories in our audio archive; or by adding to the collection of inherited recipes. Through these contributions an archive is developing in the caravan, which includes a really wide range of stories and experiences of grief and remembrance.

In this post I’m going to think about why people felt able to share these personal and emotional stories with us, and what we did to make the space feel open, non-judgemental and safe. And I’ll do this by briefly discussing three themes: micromuseums; autobiography; and senses.

Micromuseums

In his Modest Manifesto for Museums, the Turkish author Orhan Pamuk wrote:

We all know that the ordinary, everyday stories of individuals are richer, more humane, and much more joyful … It is imperative that museums become smaller, more individualistic, and cheaper. This is the only way that they will ever tell stories on a human scale. Big museums with their wide doors call upon us to forget our humanity and embrace the state and its human masses.

Pamuk’s manifesto was one influence on the caravan, and in line with his call it is small, individual and free to enter. The use of a range of personal stories of grief – mainly drawn from Ellie Harrison’s experiences, but including other people’s too – means that it is open to different interpretations and responses (emotional and conceptual), and there are many different ways in which the visitor might connect to the works.

Fiona Candlin, Professor of Museology, has discussed some of the characteristics of small museums in her book Micromuseology. Using examples of a really interesting range of small museums across the UK she identified a few common themes – many of which had a significant effect on visitor experience – and three in particular are relevant here. Firstly, they are places outside the establishment and this means that the stories they tell are more diverse, and they are able to diverge from the narratives of the nation or state. Second, they are personal projects which reflect the collecting habits and personality of one person or a small group, and they are often autobiographical. This means visitors connect to the museum in a different way, and this is aided further by the opportunities for interaction with owners, curators or staff. Visitors can develop their own interpretations and share experiences during these conversations. This means, Candlin argues, that ‘the visitors are not the passive recipients of information but actively assist in the generation and communication of knowledge’.

Perle, the caravan, is a space outside the establishment and the stories represented inside resist popular ideas about ‘normal’ grief. These stories are personal – whether drawn from Ellie’s own experiences or collected through research in archives and with participants – and they touch a range of feelings, which are often intertwined: joy, anger, sorrow, humour, nostalgia, and so on. And this did prompt really meaningful conversations with visitors, many of whom wanted to share their own experiences and their emotional responses with us. The caravan invites visitors to make a lasting contribution too: through conversations which help us thing about grief and remembrance in different ways, and through leaving comments which add to the archive. One of the really lovely things about these contributions is that in response to the question ‘where does the memory of the dead live?’ visitors often didn’t just name a place, but described a scene including activities, behaviour, food, sounds and smells.

Autobiography

I’ve already mentioned that autobiography and personal stories affected the ways that visitors engaged with Pearl. For Ellie this is part of working ethically – if you ask somebody to share a difficult or traumatic experience with you, you should be willing to give something back. But this use of autobiography also allowed visitors to connect to the work in different ways (and many people wanted to find out more about Ellie or speak to her, extending that connection further), as well as prompting them to think about grief differently.

Andrea Witcomb, Professor of Cultural Heritage and Museum Studies, has written about the powerful role that autobiography can play in museum displays. She discusses a miniature model of the Treblinka death camp, which was handmade by survivor Chaim Sztajer and donated to the Jewish Holocaust Centre in Melbourne, Australia. Witcomb argues that the use of personal testimony ‘provides an opportunity for identification, for the building of a personal link’. Visitors learn that Sztajer made the model over three and a half years in his living room and then donated it to the museum, that he was one of only seventy survivors of Treblinka, and the model figures represent his wife, daughter and friends who died in the camp. The model encourages the visitor to remember the dead but it also shows the ongoing grief of the artist; it is so emotive, Witcomb argues, because it actives ‘the expression of empathy in the present, rather than for past victims’.

The use of autobiography in the caravan similarly ‘provides a glimpse into ongoing grief’, but the desired outcome of this empathy is rather different. Ellie wanted to use autobiography to break down hierarchies between artist and visitor, and tell stories which would open a space for visitors to reflect on their own grief – in whatever form that might take. The personal connection which visitors form with these stories allows them to feel and to communicate those feelings, even when they are linked to really difficult experiences. An important example of this is the death of children – an experience which even today is often unspeakable. A number of women wrote about this experience for us, and they were perhaps empowered to do so because the caravan includes a story about stillbirth accompanied by beautiful embroidery.

Senses

The physical space inside the caravan, and the way that visitors were able to interact with the objects on display has also shaped the response. Perle is interactive: you can look through cupboards, open draws, move maps, smell the herbs… This allows the visitor to both feel curiosity and to satisfy it.

Art historian Stephen Bann writes that curiosity leads to surprise, delight and amazement, and, more importantly, it leaves room for the visitor to imagine and form their own stories, historical narratives and categories: ‘Curiosity has the valuable role of signalling to us that the object on display is invariably a nexus of interrelated meanings – which may be quite discordant – rather than a staging post on a well trodden route through history’. Similarly, the features of the caravan - the arrangement of objects, the action of opening cupboards and drawers - allow the visitor to experience the stories of grief displayed as well as their own emotions in different ways. And touch is closely linked to emotions too. Psychologists Charles Spence and Alberto Gallace have found that touch and multisensory stimulation ‘can lead to a more profound and emotional contact with the art’.

So in lots of different ways the caravan allows visitors to identify and connect with the grief stories that it contains, but it also gives agency - to interpret stories in different ways and to feel different emotions. The form of the caravan helps too: it is small, visitors enter alone or in very small groups, they are then enclosed and not watched, the space feels safe, and on a shelf there are tissues as well as tokens which visitors can use to ask for hugs from the project team. The space inside the caravan is open, it’s non-judgemental, and it cares.

Did you visit Perle during the Journey with Absent Friends? You can share your experience in the comments section below. And keep an eye on the Grief Series website for upcoming locations and events.