Working with family historians – remembering and forgetting our ancestors

Laura King, University of Leeds

What can family history tell us about how we remember?

As we’ve worked with family historians over the past year, exploring their memories and research into their family’s past, we’ve learnt a lot. Through interviews, using their family ‘archives’, the sharing of research documents (such as family trees and notes), and the production of their own writing (blog posts and booklets summarising their histories), we know lots about the history of many families over many generations. We’ve also learnt a lot about processes of remembering (and forgetting) and have been exploring the things, places and stories that travel through different generations of a family, shaping their memories of past ancestors and their family’s sense of identity.

Any collaboration, though, has to be two-way. And in our last catch up, we reviewed what the family historians had got out of us working together. Whilst other fascinating collaborations have focused on very specific experiences and institutions, such as Tanya Evans’ work with families who had come into contact with the Benevolent Society in Australia, and Jane McCabe’s project exploring the histories of children who had spent time in the Kalimpong ‘Graham’s Homes’, we’ve been exploring how family and academic historians (which are by no means mutually exclusive groups!) might work together on broader histories – such as of family life, death and dying, health, and housing. What can both groups get out of this kind of work?

We got lots of research data. We were able access the particular expertise our group offered: firstly as historians of their own families, they could reflect on and tell us about why they thought things were and weren’t remembered in their own families. And as members of those families, they knew lots about the significance of different places, objects, stories. Because their family archives were still held within the family, we could learn so much more about their significance and meaning than if they had been placed in an archive or museum. There are many layers to the information and knowledge we could learn from this group.

For our family historians, it seemed three things were useful in our collaboration. Firstly, there were the practical things – we had helped them access academic expertise on various aspects of history, from mining to the First World War, thereby helping them contextualise the lives of their ancestors. We also offered visits to local libraries and archives and training sessions, in a range of subjects from understanding causes of death to looking after family archive items.

Secondly, there was the sense of camaraderie and support getting together each month had provided – and this was key to keeping motivated with their research. One historian wrote the project had ‘revived my interest and enthusiasm for family history’, whilst another commented that they had valued ‘having the opportunity to share my research & inspiring me to sort it out’.

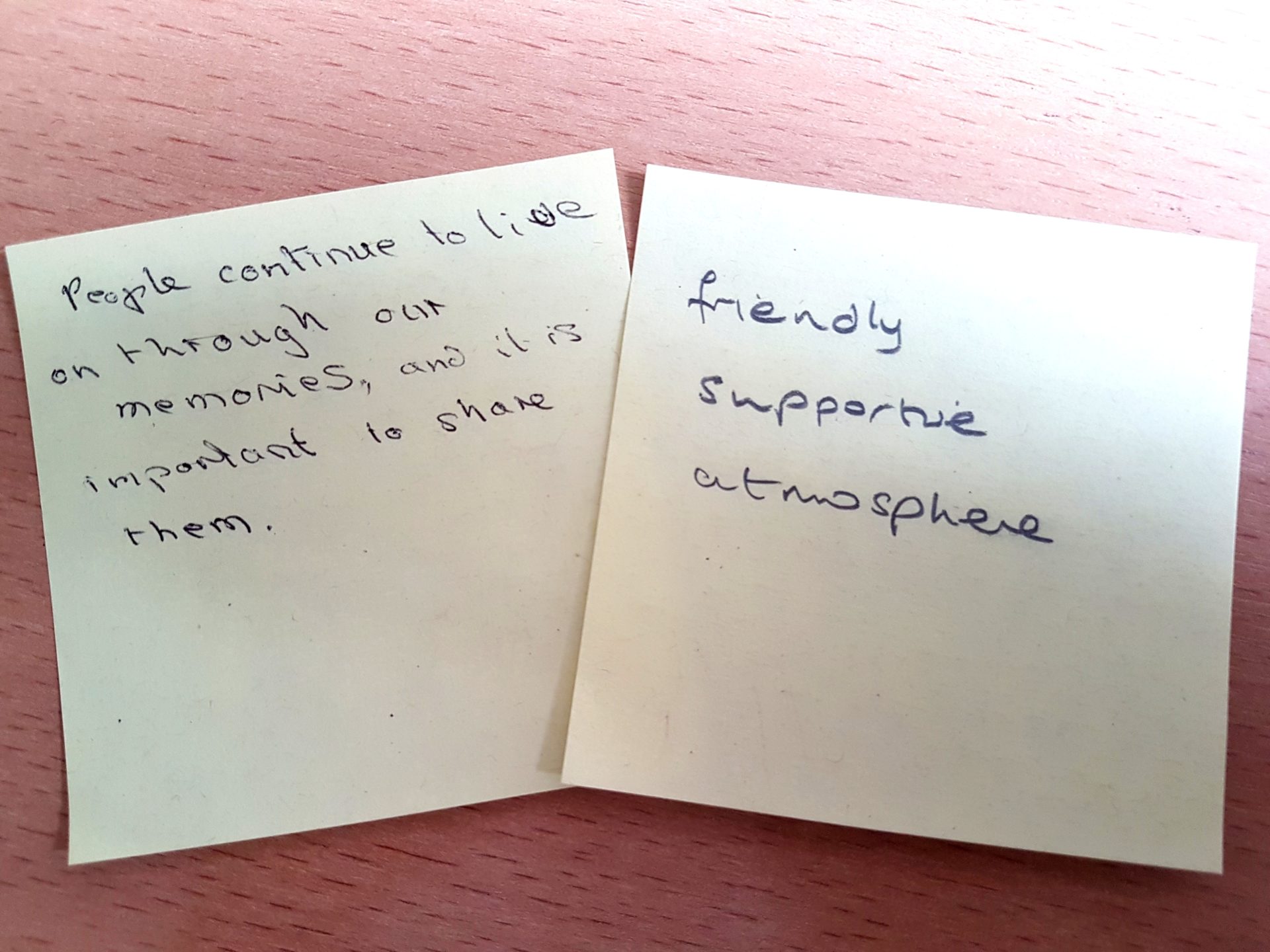

Thirdly, and perhaps most interesting to me, was the comments which hinted at the way in which the family historians had reflected on their understanding of their family’s history, and how to preserve it for future generations. One family historian mentioned that she now plans to write up an account of her mother’s life, and memories of her mother, to pass on to her son – as otherwise these memories would be lost. Another commented, when we asked what they had got out of working with us, that ‘people continue to live on through our memories, and it is important to share them’. And another wrote that the project had ‘made me look again at how I remember family members & re-evaluate certain events’. One member of the group described how it had deepened her understanding of history. They had also valued simply being listened to and taken seriously, in an academic setting.

Thirdly, and perhaps most interesting to me, was the comments which hinted at the way in which the family historians had reflected on their understanding of their family’s history, and how to preserve it for future generations. One family historian mentioned that she now plans to write up an account of her mother’s life, and memories of her mother, to pass on to her son – as otherwise these memories would be lost. Another commented, when we asked what they had got out of working with us, that ‘people continue to live on through our memories, and it is important to share them’. And another wrote that the project had ‘made me look again at how I remember family members & re-evaluate certain events’. One member of the group described how it had deepened her understanding of history. They had also valued simply being listened to and taken seriously, in an academic setting.

What I think this tells us is that such collaborations can be really mutually beneficial – even if the outcomes are different for each side. We weren’t working towards the same aim in our respective research projects; as an academic research project we’re interested in the social history of dying and remembrance. And each family historian is concerned with furthering their research into their family in some way, and perhaps passing that on to other relatives. But in working towards our quite different aims, there has been useful potential for collaboration.

We’re going to be exploring this notion further in a workshop on 14th July. The programme features a range of speakers who have worked in projects with some element of collaboration between family historians and academics historians – Tanya Evans as our keynote, with shorter talks from Julia Laite who is finding ways to create spaces for family historians and academics to share knowledge and exploring the inequalities in the family history landscape; Mike Esbester who works on the history of the railways; Cynthia Brown and Mary Stewart who will reflect on the overlaps between oral history and family history; and Nick Barratt, who has worked with a wide range of historians in his work on Who Do You Think You Are, and who is currently exploring the social and health benefits of family history. We will have a workshop discussion session in which we will be presenting the work of our Living with Dying collaboration, and showcasing the family histories we’ve researched. And our panel, involving historians from a wide range of backgrounds, will reflect on the potential for collaborative work in the future.

The workshop is now fully booked, but we’d love to hear from others about the value/potential of such collaborative projects and what different historians get out of working with others. Please do join the discussion in the comments below.