Inheritance Facts?

A guest blog from Paul Cave

When I was a child, my favourite thing in the world was to draw. “I don’t know where you get it from” my parents would say as I bombarded them with sketches to critique (I’m sure they wished at times that I hadn’t got it from anywhere). My Great Uncle Ernest painted though, and when he found out that I liked to draw, would occasionally show me new techniques. I remember assuming that I must owe my love of art to him. But he wasn’t a blood relation – he’d married my Grandma’s sister. I felt quite disappointed when I realised this.

If not from my Great Uncle Ernest, then where did this desire to draw come from? Of course the bigger question is: why was I so keen to see my childhood hobby as a mystery that could only be explained by inheritance? Wasn’t it possible that drawing was something that I came to myself? And wasn’t that more interesting anyway? (And shouldn’t I be outside playing with my friends from junior school instead of pondering the nature of consanguinity?! I was quite the sensitive wee kid).

I guess there is something beguiling about the thought of being an extension of things that have gone before. We are not just us. We have our Mother’s hair, our Grandad’s sense of humour. And researching our family trees can give us more to cling to. My Great Grandad was a printer – I work in a library; my Father’s family came from Ireland and loved music – I love music; many of my relatives worked in the textile industry – I… wear clothes?

* * *

Rather greedily I had four grandads, although I never knew my Dad’s Dad, Grandad Leslie, as he passed away before I was born. My parents talked about him often, and it wasn’t until I was 4 or 5 that I realised that I would never meet him. The realisation came to me in bed one night and I cried. I cried so long and hard that my Dad came upstairs to see what was wrong. I still remember the look on his face when I told him why I was crying.

Grandad Bill married my Dad’s Mum, Grandma Mary, when I was a baby. He was a jolly rotund chap with a love for gardening. He laughed as we played dominoes. He laughed as he showed me how to shell peas. He still laughed when my Grandma Mary’s untimely death left him alone in their bungalow.

My ‘Uncle’ Fred lived with my Mum’s Mum - plain old Grandma. I didn’t really understand why he was my ‘Uncle’, or why he had another house 100 yards away from my Grandma’s which he never seemed to spend any time in. He too liked gardening and, despite his gruff exterior, he took time to play toy cars with me and gave me piggybacks.

And then there was my Grandad Stone. He was my Mum’s Dad and I knew I loved him because my Mum told me I did. He seemed a lot older and more serious than my other Grandads and, uniquely amongst them, was referred to by his surname rather than Christian name – Grandad Stone rather than Grandad Phillip.

He wore brown and beige and came to our house once a week, where he would spend several hours complaining, before my Mum gave him a lift home. He complained about the weather, complained about my Mum’s cooking and complained about the television. But most of all he complained about his health. He carried a cloth handkerchief with him to catch the thick globules of sputum he produced at five minute intervals and he wheezed at every minor exertion. A man of few words but much phlegm. I could have been more sympathetic (I should have been more sympathetic) but I was a small boy with a headful of Lego and, although I loved-him-because-my-Mum-told-me-I-did, I would much rather be in a different room, or preferably at my friend Johnny’s house, whenever he came round.

My Mum sometimes took me with her when she went to clean at my Grandad Stone’s. When I was very young he lived in a damp tower block in Holbeck. My Mum’s inner snob rose to the surface as we rushed up to floor 831 in the graffiti-strewn lift. Grandad Stone was never in when we went round to clean, cleaning presumably being ‘women’s work’, and besides, there were pints to be drunk. It never occurred to me that he would share these pints with friends, until I saw a photo propped up on the mahogany cabinet my Mum was dusting. In the photo, two men stood laughing either side of a brown and beige-clad man who looked exactly like Grandad Stone… but he was laughing too.

Later I found out that he’d built the mahogany cabinet himself, along with the table and chairs that sat incongruously in his pokey flat. They looked even more out of place in the back-to-back terrace he rented in Morley towards the end of the 1980s. Closer to my Mum and closer to the pub. Although, by then, he’d stopped going to the pub as far as I could tell. He struggled to walk more than a few feet and his visits to our house briefly increased, much to the chagrin of all parties.

On 26 February 1990, my Mum went to my Grandad Stone’s house to clean. She found him dead in his armchair. I’d gone to Johnny’s house to play after school. My Dad came round to tell me, and to ask Johnny’s parents if I could stay with them for a few hours until he and Mum finished dealing with the ambulance. Despite the sadness I’d felt years earlier when I’d realised that I would never see my Grandad Leslie, I failed to comprehend what had happened. I think I may have actually been a tiny bit excited about being allowed to stay up late and watch Star Wars on video. When I finally returned home, my Mum was fussing around in the kitchen. “You’re taking it well” I said. It seemed like the kind of thing a grown-up would say. My Mum explained that death was something you had to deal with as you got older. I thought about that when she died in 2011 and I was the one in the kitchen, mechanically making cups of tea.

* * *

I learnt a lot more about Grandad Stone when I began researching my family history in 2005. My parents told me that he’d lived with us when I was a baby, having separated from my Grandma. I found out that he’d come from a comparatively wealthy family, something which explained as much about my Mum’s occasional bouts of snobbery as it did my Grandad’s resentment at the ‘reduced circumstances’ he found himself in towards the end of his life. And I found out that he’d been a mechanic in the Royal Air Force during the Second World War. Actually, I’d always known that he was in the RAF but, unlike my Grandad Bill, who was happy to regale me with tales of his misadventures in the Fleet Air Arm, stationed in Ceylon during the war; or my Uncle Fred who stoically batted away questions of a similar nature; Grandad Stone acted as though it had never happened. Apparently, when he’d had a few beers, he’d talked to my Dad about being at Monte Cassino during the Allied invasion of Italy, and he’d complained (no surprise there) about maintaining “kites” in the heat of North Africa, but he’d never said a word to me, despite knowing how interested I was in the simple ‘goodies vs baddies’ movie-version of WWII I’d assimilated as a child. Or maybe because of.

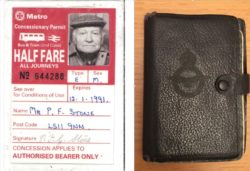

As I hunted for clues to the past in my parent’s loft, I came across a box of photographs and bric-a-brac that we’d inherited following Grandad Stone’s death. Along with carpentry tools and a bus pass, showing the grumpy brown and beige old man I once knew, were photos of a young chap in uniform, posing in the desert with an anti-aircraft gun. In one he looks into the distance, smiling, in another he squints through the gun sight, aiming at some imaginary foes. My Grandad looks youthful and, in a picture of him and two chums exaggeratingly upending beer bottles for comic effect, happy.

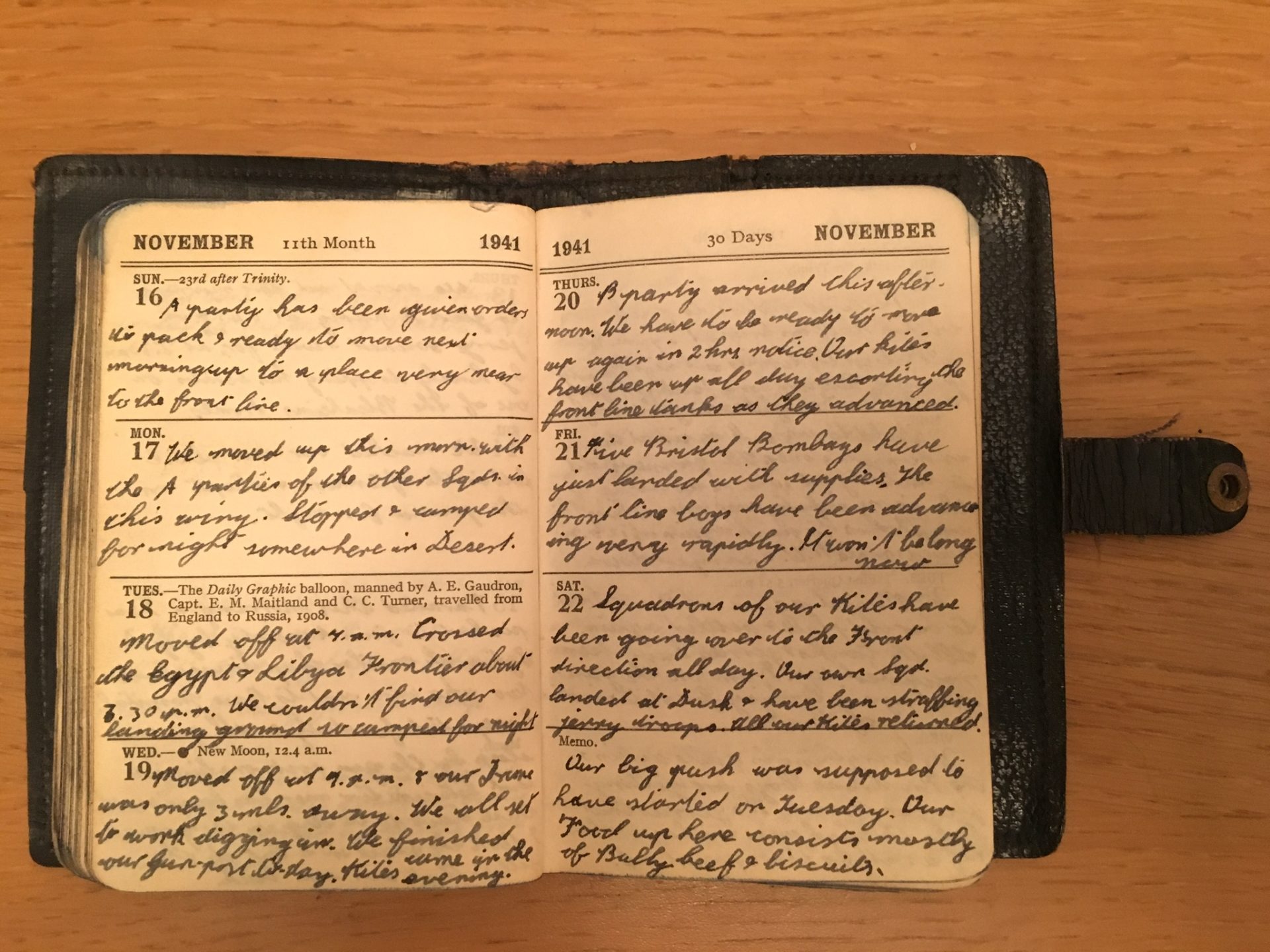

And in a corner of the box was a diary. A faux leather cover, embossed with an RAF crest, which opened to reveal ‘The Royal Air Force and Dominion Air Forces Diary, 1941’. On the second page, Grandad had written “no.1356453 LAC P. Stone, 260 Squadron, RAF”.

He was no Samuel Pepys. Most pages are blank and, even when he did write an entry, Grandad generally kept it brief. “At Freetown” reads the entry for Sunday 8 June. And the entry for Monday 9 June. And the entry for 10 June. This continues until 13 June when he writes “At Freetown. Attacked by a Jerry kite. Bombs dropped.” Which very much sums up the diary – a mixture of mundanity and fear.

The following day, the diary once again reads “At Freetown”. At the time Grandad was 20 years, 4 months and 26 days old, confined to a troop ship in a West African harbour, under intermittent bomb attack, waiting to go to war. When I was 20 years, 4 months and 26 days old I had just started an English Literature and Philosophy degree at the University of Leeds and the only thing I was waiting to go to was a gig by Britpop also-rans Gene down the road at Leeds Met.

Thanks to the internet, I can find out all there is to know about convoy WS.8B which took my Grandad to Africa, and the ship, MV Christiaan Huygens, that he sailed on. I know that, during the period covered by the diary, No. 260 Squadron operated Hawker Hurricane Mk Is and can read about the Ecuador-Peruvian war, which he references in an entry on 7 July while waiting in another harbour, this time in South Africa. But the infrequent personal entries are the most interesting. After noting that Ecuador and Peru were at war and that he’d be “going on another boat tomorrow”, a more wobbly sentence, written with a different pen, states “My pal and I were invited out in the evening by some swell folks and had a grand time”. The thought of my brown and beige Grandad painting Durban red is hard to process.

On 20 October 1999, I celebrated my twenty-first birthday in ‘legendary’ Leeds nightclub, Majestyk. After depositing a large chunk of my student loan at the bar in return for too many/not enough pints of, what a 90s advertising agency optimistically described as “the amber nectar”, I stood on the balcony, faced the crowd of Emmerdale bit part actors, Leeds United reserve team players and increasingly aggressive young gentlemen out ‘on the pull’, and sang along to “Bohemian Rhapsody” like some sort of fluorescent jelly baby.

58 years earlier, on 20 October 1941, Grandad was in the Sinai Desert, spending the night at a “Greek RAF camp”. He was on his way to the frontline, where he would soon take part in Operation Crusader, a plan to relieve the siege of Tobruk which would become the first major British victory over German ground forces during the war. The contrast in our young lives couldn’t be more stark.

On Saturday 29 November Grandad Stone wrote:

One of our Sqd. Kites was attacked by three Mess. 109s this afternoon. The pilot shot one down and came back ok except for a few cannon shell holes in his fuselage.

We later moved off and 30 tanks, with 4 lorries to each carrying German troops, nearly ran into us. Lucky for us the desert is a big place.

A few days later, on Tuesday 2 December, the diary ends. My Grandad notes that there is only enough water for “half a mug full of tea with each meal” and that “everyone has nearly grown beards and the sand storms are making us filthy”.

***

After reading his diary I think I understand my Grandad more, and feel rather guilty for viewing him in such one-dimensional terms when I was a child. I know I’m incredibly lucky that, along with photographs and various other personal items, I have his diary. I wish he’d lived long enough for us to have a proper relationship though, rather than having to look to a handful of laconic jottings for answers to questions I never thought to ask.

* * *

I recently decided that I needed some new trainers (in the same way that the Queen needs more hats). Negotiating the Saturday hordes, I entered a shoe shop and scanned the shelves, eventually coming across a pair I liked. Adidas. Classic trefoil logo. Suede upper. I wasn’t keen on the colour though: a kind of watery blue. “Excuse me”, I said to a passing shop assistant, “do you have these in brown and beige?”