Remembering the Dead

Laura King, University of Leeds

What objects do you hold on to because they remind you of someone you’ve lost? Where do those memories of the deceased live? What kind of things do we do to keep their memories alive?

Last week saw the annual Mexican Día de los Muertos, or Day of the Dead, celebrations, which our wonderful guest blogger Laura Loyola described in her recent post. And this week, as the many poppies pinned to lapels, shirts and bags remind us, is the biggest event of remembrance of the dead in the British calendar. Both of these events help us take a moment to remember those who have died, whether we knew them or not. But what does remembrance look like in everyday, family life, throughout the year?

One of the major questions of this research is how people remember the dead within their day-to-day lives, and how that’s changed over the twentieth century. Through my research into autobiographies, as well as our public engagement work, it’s become clear that there are a number of key ways in which individuals and families remember their dead in Britain. These are often used in tandem, but include:

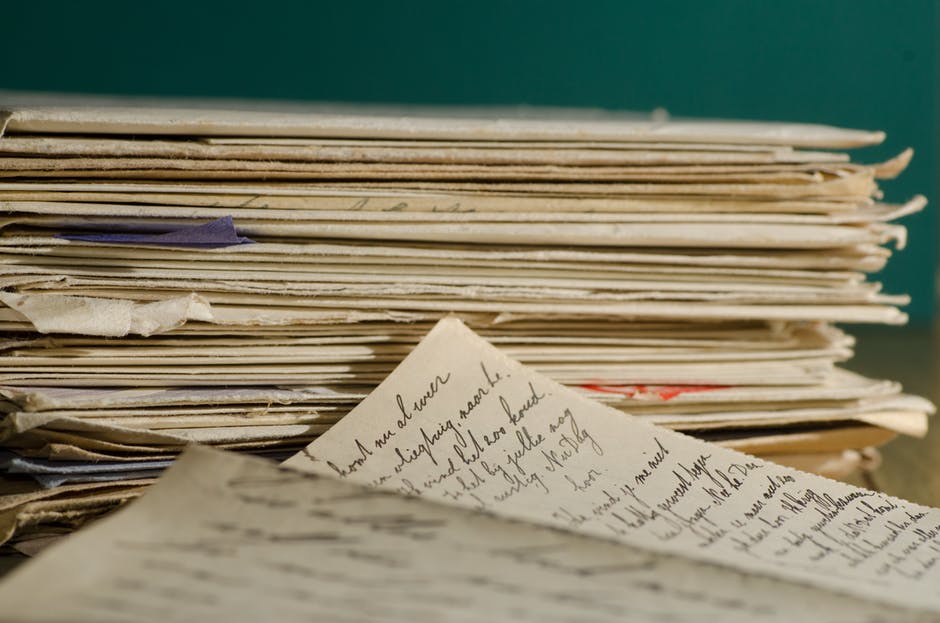

Objects. Whether these are created specifically in order to remember or something incidental that becomes significant because of a death, things are special in processes of remembrance. Objects have often been created in response to a death – think about the mourning brooches of the Victorians to ceramics and vinyl records made from cremation ashes today. But beyond that, any everyday object might become significant – it could be jewellery or precious personal items passed down in a will, or as diverse as documents such as letters, books, cutlery, garden tools, clothing or furniture. These can be things that previously belonged to a person who died, or something associated with them more tangentially. From Molly who designed the house she built to incorporate her late husband’s furniture in the 1920s, to Suzie’s Traveller family who spent years tracking down and buying back their dead father’s wagon, the autobiographies I’ve studied contain numerous examples of the multitude of objects, big and small, which become significant in remembrance.

Places. The place of burial or the scattering of ashes could become a sacred place to remember, as could the home of a person who died. But again, the way in which people use places in their remembrance is broad. Favourite holiday destinations are a common example. But other examples of favourite places can also be significant, such as Brian who occasionally revisited the favourite spot in the theatre his father used to inhabit during the cheap classical concerts on Monday evenings in the 1930s. Indeed, inhabiting a space can provoke intense emotions and the ability to remember those who have died in a more visceral way. For example, when Ralph returned to the streets he grew up in East London, the space tricked him into ‘seeing’ his deceased grandmother and grandfather again.

Practices and rituals. Often in conjunction with the above, I have found many examples of individuals and families doing something to remember those who have died. This might be a regular visit to a grave, such as Ted’s mother, who used to take him as a child to visit his sister’s grave, where she would ‘clip the grass round the tiny grave, plant bulbs, arrange cut flowers in a jar’. And Elin, a refugee from Estonia, remembered that every visit to their local town in Estonia with her grandmother included stopping at her grandfather’s memorial, so her grandmother could ‘exchange a few words with him’. However, remembering could also be the practice of regularly telling stories about relatives who had died. Jo, growing up in the Black Country in the middle of the twentieth century, liked nothing better than hearing her mother’s soft voice recalling various relatives both dead and alive, and their life stories. The act of writing is an extension of this, capturing those stories in a more permanent form. This is described in the introduction to the Knowles' family history, in which they ask ‘How can we stop our own loved ones from fading away like melting snow?’ – and answer by writing their memories down.

Senses and emotions. When our deceased loved ones pop into our minds, we don’t always know why, and of course remembering doesn’t have to be tied to a particular object, place or act at all. But sometimes a feeling, a smell or a sound, and particularly music, can trigger thoughts about someone we’ve lost. In our recent public engagement events, those we’ve talked to have highlighted this a lot – the smell of pipe tobacco, soap, cakes baking or perfume can bring someone into our head, or a particular song or type of music can take us right back to a time we spent with them. How has this changed over time?

Next year, we’ll be hosting an exhibition at Abbey House Museum on remembrance, and what that means to a range of different communities in the past and present. How do you remember those you have lost? Please do share your experiences in the comments section below, or get in touch with us if you’d like to know more.

Autobiographies referred to:

Molly Hughes, A London Family Between the Wars (Oxford, 1940/1979)

Suzie Lee/Essex County Council Learning Services, One in a Million: A story of hardship, endurance and triumph in a Traveller family (Chelmsford, 1999)

Bryan Magee, Clouds of Glory: A Hoxton Childhood (London, 2004)

Ralph Finn, Spring in Aldgate (London, 1968)

Ted Walker, The High Path (London, 1982)

Elin Toona Gottschalk, Into Exile: a life story of war and peace (Lakeshore Press, 2013)

Jo Stafford, Light in the Dust (Stourbridge, 1990/1995)

Anon/The Knowles Family, ‘Won’t Someone Please Remember the Knowles Family of Knostrop?’ (unpublished, Leeds Central Library Local and Family History LQP B KNO)