A family of 25 whose story is told through the Leeds General Cemetery

By Imogen Gerard and Kelsie Root

Burials can reveal a lot about a person's life: a fact which historians like to take advantage of. The site of burial can indicate a person's religion: most people buried in churchyards will have been members of that congregation, whilst people buried in general cemeteries were often non-conformists. The size and extravagance of their monument may tell you something about the wealth of that person's family. If their burial plot is shared with other people, this can help you to deduce who their family members were.

The Leeds General Cemetery (now known as St George's Field and located on the University of Leeds campus) was open for burials between 1835 and 1969. Detailed records of who was interred at this cemetery were kept and have been recently digitised. The burial records can be browsed, searched and accessed online here.

Thanks to this cemetery's burial records, we have been able to uncover the story of a family who used the Leeds General Cemetery to bury their loved ones throughout the 130 year period the cemetery was open. At least 25 people in the Frankland family are buried at the the Leeds General Cemetery in 6 different burial plots.

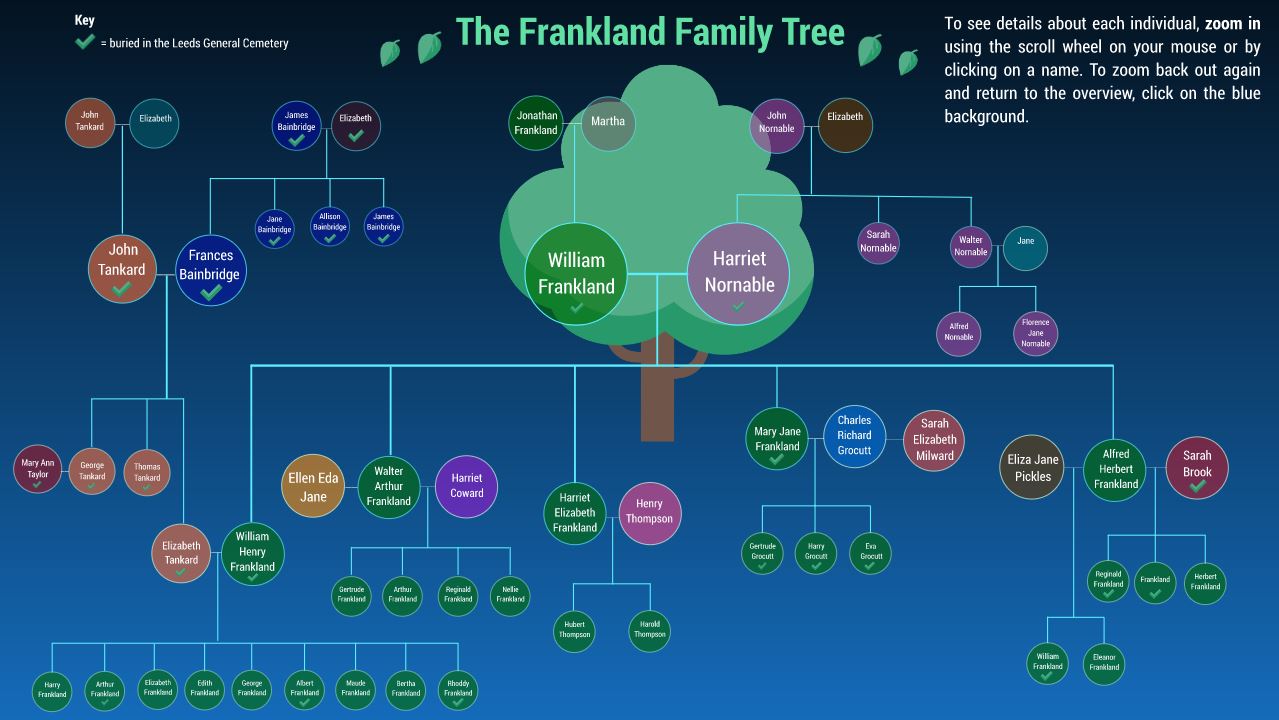

- To see who the Frankland family were and how they are all related, view this family tree. Zoom in to learn details about each individual, using the scroll wheel on your mouse or by clicking on a name. The 25 people marked with a tick are those that are interred at the Leeds General Cemetery.

- To see the chronological order in which these people entered the cemetery, and the different plots in which they were buried, have a look at this timeline. You can zoom in on any of the plots for more details.

Our interest in this family was first piqued when we noticed the occupation ‘casket manufacturer’ in the burial registers. The entry in question was Sarah Frankland, who died in 1888 and whose father’s occupation was recorded as ‘casket manufacturer’.

As it turned out, we had trouble tracing Sarah’s parents’ and their business, primarily because Sarah’s father had a very common name - John Brook. Nevertheless, Sarah Frankland turned out to be a fruitful starting point for an investigation into the use of the Leeds General Cemetery by one family across several generations.

As it turned out, we had trouble tracing Sarah’s parents’ and their business, primarily because Sarah’s father had a very common name - John Brook. Nevertheless, Sarah Frankland turned out to be a fruitful starting point for an investigation into the use of the Leeds General Cemetery by one family across several generations.

We selected Sarah Frankland’s plot number, 12,787, to see who else she was buried with. There were 5 other people in the plot, 4 of whom had the same surname. This was a strong indicator that the plot in question was a family plot and that the people in it were related. Using genealogical website such as Ancestry.com and FreeBMD we began to research the links between the people buried in the same plot. We discovered Sarah was buried with her child, her parents-in-law, her husband’s niece, and a child from her husband’s second marriage following her own death. Delving deeper, we pieced together the story of Sarah and her family’s tragic and fascinating life:

Sarah Brook was born in Halifax in 1859. By 1884 she was living on Lovell Road in Little London in Leeds. Also living on Lovell Road was Alfred Herbert Frankland, the man Sarah went on to marry. Our theory is that the couple met because they were neighbours living on the same road.

Alfred was one year older than Sarah and worked as a commercial traveller. The pair were married on 20 November 1884 in St Luke's Church, Leeds. Their first child Reginald was born in around May 1885. He died only 20 months later in January 1887 from bronchitis. Reginald was buried in plot 12,787 in the Leeds General Cemetery where Alfred’s parents had already been laid to rest.

Tragically, only a couple months later in March 1887, Sarah had a stillborn baby. It is worth noting that this infant was buried in a common grave. This type of grave was owned by the cemetery. Common graves were the cheapest graves available, used for unrelated people who could not afford a private plot. The Frankland’s decision to bury their stillborn infant in a common grave, when only 3 months earlier they had buried their first born child in the family plot, tells us about 19th century social attitudes towards stillbirths. Socially, stillborn babies were treated very differently to other infant and child deaths. Stillborn infants were not named or commemorated with funerals. The registration of stillborn babies wasn’t legally required at all in England until 1926. The Frankland family’s burial practices exemplify these attitudes. We can infer that they felt it was less necessary to pay for a burial in a private family plot for their stillborn infant.

Fortunes for the Frankland family didn’t improve for a while. One year after the stillbirth in March 1888, Sarah died of fever. She joined Reginald and Alfred’s parents in plot 12,787 in the Leeds General Cemetery. It may be that that Sarah’s death was the result of childbirth. The birth of Alfred’s son, Herbert, was registered in the quarter April-May-June. It is likely that Herbert was Sarah and Alfred’s third child, and that she gave birth to him just before she died. Her cause of death, fever, may well have been puerperal fever resulting from infection following childbirth. So by 1888 Sarah’s widower, Alfred Herbert Frankland, had lost two children and his wife in just over the space of one year and was left caring for a newborn.

Later that year, on 22 December 1888, Alfred was re-married to Eliza Jane Pickles, who was from Huddersfield. This may seem fairly soon after Sarah’s death, but given Alfred’s circumstances, it easy to understand why a quick second marriage was necessary. The need for an immediate wedding becomes even clearer, given that the couple’s first child, William, was born in April 1889. Eliza would have been approximately 5 months pregnant at their wedding.

The painful reality of the 19th century’s high infant mortality rates is all to apparent when considering the case of the Frankland family. Eliza and Alfred’s first born, William, died when he 3 months old. The cause of death was recorded as diarrhoea, which was usually a result of poor sanitation and contaminated water.

Thankfully, after this point things begin to look up for the Franklands. Eliza and Alfred had a daughter, named Eleanor, in 1892. Census records show that in 1901 and 1911 Eliza, Alfred, Herbert and Eleanor all lived together as a family. Eleanor lived a long life, dying in 1966 aged 74. Her grave can be found at All Saints' Church Cemetery, Huntington, Yorkshire where she is buried with her husband.

Thankfully, after this point things begin to look up for the Franklands. Eliza and Alfred had a daughter, named Eleanor, in 1892. Census records show that in 1901 and 1911 Eliza, Alfred, Herbert and Eleanor all lived together as a family. Eleanor lived a long life, dying in 1966 aged 74. Her grave can be found at All Saints' Church Cemetery, Huntington, Yorkshire where she is buried with her husband.

Analysing the life of the casket manufacturer's daughter illuminated a colourful story. The narrative of the Franklands included love found between neighbours living on the same road, the tragedy of 19th century infant mortality, a child conceived out of wedlock and a hasty but lasting second marriage.

Three people who are mentioned in this story are buried in the plot 12,787 of the Leeds General Cemetery: the casket manufacturer's daughter herself, Sarah; her son, Reginald; and her husband’s son, William. We decided to investigate the other 3 people sharing this plot of ground - Alfred’s parents and his niece. By researching these people, we were able to trace the family back a couple generations, as displayed in the family tree.

Alfred’s older brother, named William Henry Frankland, appears to be the reason that so many of the Frankland family are buried in the Leeds General Cemetery. William Henry’s wife had grandparents, an aunt, uncles and a brother buried in this cemetery. So when one of William Henry’s 9 children died (Arthur Frankland), the child was buried at the LGC beside his mother’s relatives.

To find out more about the Franklands, do explore our interactive family tree. As you do so, look out for the following trends:

- The repeated use of certain family names

- Instances in which children worked in the same profession as their parents

- The different places where the families lived (Kelsie Root, one of the LGC student interns, noticed that Harry Grocutt who features on this family tree, lived at the same address in Leeds as she lived last year!)

- Finally, can you spot the member of this family who emigrated to Australia?

And remember you can view the order in which this family was buried in the cemetery over time and the different plots they were buried in by viewing this timeline.

Let us know what you discover in the comments!