Class beneath the Grass: Segregation within Cemeteries

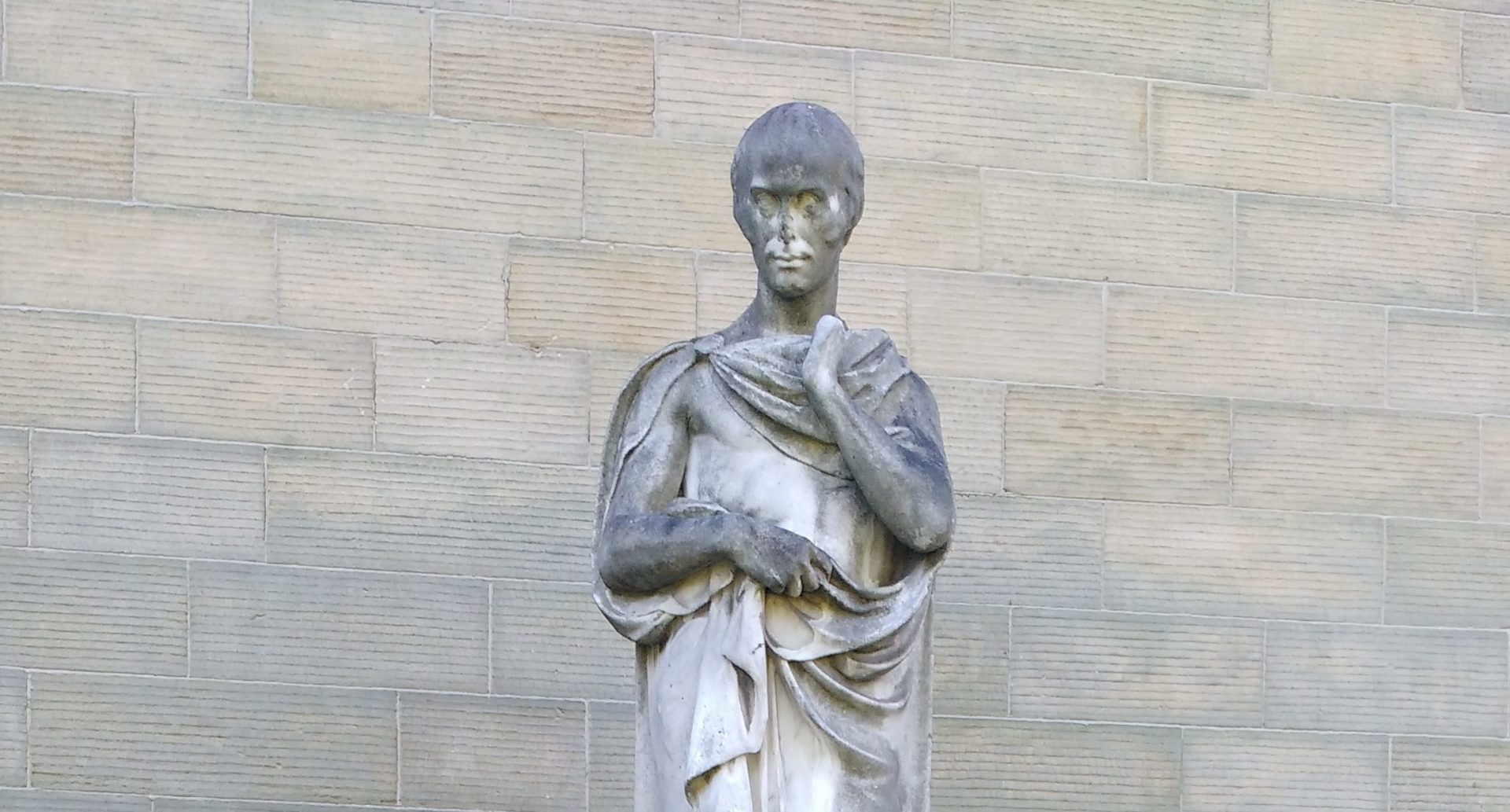

Image: Monument of Michael Thomas Sadler (1780-1835), paid for by voluntary subscription. This statue stands next to the cemetery chapel in St George’s Field.

By Imogen Gerard and Kelsie Root

Does everyone deserve a dignified burial? What impact should class and wealth have on burial rites? In our previous blog post in the Leeds General Cemetery series, we looked at the ways in which different religious beliefs affected burials Leeds General Cemetery. In this blog, we’ll discover how social class had just as strong an impact on burial as religion.

The allocation of burial plots was one of the most obvious ways that social class affected burial. Some areas of the cemetery attracted a particular clientele. This is clear from plot numbers of buried individuals recorded as ‘gentlemen’. ‘Gentleman’, as an occupation, indicates that someone generates their income through owning land or investments rather than having a ‘day job’. The vast majority of gentlemen within the cemetery are buried in plot numbers 8,000 to 10,000, clustered around the chapel in the centre of the cemetery. These plots were more expensive to buy and records show that these graves had some of the more impressive monuments available.

For wealthy families, funerals could be a no-expenses-spared event. Funerals were a chance to mourn the deceased and to celebrate their life, but also carried heavy expectations, both religiously and socially.

Stringent ideas about the “correct and proper” way to mourn produced a huge array of ways to personalise a burial ceremony. Wealthy families with the means to do so could pay extra to have their relative buried nine feet deep, rather than the standard six feet, in an effort to further protect the body itself from the weather, animals or grave robbers. Some cemeteries, such as Methodist Chapel in Brunswick, offered a boggling array of extras, with mourners charged per psalm and per bell ring. Mourners could even be fined for going over the allotted time for the funeral, with the proceeds being donated to the local school.

The headstone was often the costliest single part of organising a burial. Many cemeteries employed their own stonemasons who offered a variety of stone and charged per line of text. You could also opt to adorn the headstone with carvings of angels, saints or symbols. The various shapes and carvings all carried meaning to a contemporary viewer: a broken pillar meant the deceased had died suddenly at a young age, a carving of a lamb suggested they were a pious Christian in life. Some examples of these symbols still exist the Leeds General Cemetery today.

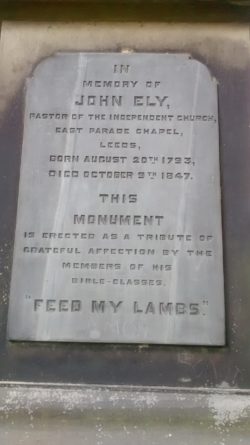

One example of a particularly public, though not necessarily extravagant, funeral was that of Edward Baines Junior, who died in 1890. Baines was well-known both locally and nationally for his piety and his philanthropy, particularly in Leeds. His funeral was a large and very public affair, with hundreds gathering at his Nonconformist church, East Parade Congregational Chapel, followed by a half-mile long procession to Leeds General Cemetery, with hundreds of people turning out to watch him be carried to his final resting place. This illustrates the intense social and religious value that was placed on public mourning towards the end of the 1800s.

One example of a particularly public, though not necessarily extravagant, funeral was that of Edward Baines Junior, who died in 1890. Baines was well-known both locally and nationally for his piety and his philanthropy, particularly in Leeds. His funeral was a large and very public affair, with hundreds gathering at his Nonconformist church, East Parade Congregational Chapel, followed by a half-mile long procession to Leeds General Cemetery, with hundreds of people turning out to watch him be carried to his final resting place. This illustrates the intense social and religious value that was placed on public mourning towards the end of the 1800s.

Images showing a grave monument in the shape of pillar, and a close-up image of one of the inscriptions upon it.

Poorer families wanted to give their loved ones a proper funeral just as wealthier families did. However, costs could be huge. A burial in a high-status vault at the LGC could cost £4 5 shillings and 5 pence, far exceeding an average labourer’s monthly wage. Even a basic burial could include charges for transporting the body, for a shroud and coffin, for a minister to lead the service, for the digging of a grave and the removal of the extra earth.

Poorer families wanted to give their loved ones a proper funeral just as wealthier families did. However, costs could be huge. A burial in a high-status vault at the LGC could cost £4 5 shillings and 5 pence, far exceeding an average labourer’s monthly wage. Even a basic burial could include charges for transporting the body, for a shroud and coffin, for a minister to lead the service, for the digging of a grave and the removal of the extra earth.

Further, organising a funeral was a lengthy process. The organiser was expected to visit the cemetery within a few days of the death and pay for the funeral upfront, in full. The price lists could be several pages long and contain a multitude of rules about who could be buried in the cemetery. These lists would have been complex to any reader, but could have been especially intimidating to poorer organisers, who were likely to have limited literacy.

Concerns about the ability of the working classes to access proper burials were widespread, as is represented in both the government work and the popular fiction of the era. Edwin Chadwick, a noted social reformer, authored a report on the burial practises of the working classes, concluding that the high costs of burying the dead were leading some poorer households to hold on to the remains of loved ones for weeks in order to save up money for the funeral they wanted. Elizabeth Gaskell’s novel Mary Barton, published in 1848, provides some examples working-class experiences of funerary rites in the Victorian era. The widow of the character Mr. Ogden is goaded into overspending by undertakers who convince her that any less is disrespectful to her husband’s memory, while the destitute labourer Davenport is buried a pauper in a mass grave ‘only a foot or two from the surface’ with no headstone or lasting memorial.

These worries were also on the minds of those running the Leeds General Cemetery. Aware that costs were preventing decent interment of the less well-off residents of Leeds, Reverend James Rawson wrote to the committee in 1842. He asked that the south-eastern corner of the cemetery be set aside solely to provide low-cost burials for children of the poor. At that time, the area was being used as a small garden by another shareholder, but it was quickly turned over to Rawson’s suggested purpose.

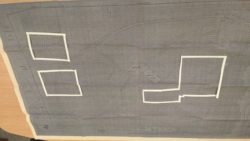

Perhaps as a consequence of this, the southeast area of the cemetery came to contain a large number of working-class individuals. The image below shows the plan of the cemetery, with the chapel in the centre. The two squares on the left hand side show plots predominantly containing labourers, whereas the shape of the right side, wrapped around the chapel, indicates the sites of gentlemen’s graves.

Image reproduced with the permission of Special Collections, Leeds University Library. Item reference: MS 421/3/7, Burial Plot Map of the Leeds General Cemetery site: https://library.leeds.ac.uk/special-collections-explore/484414

Overall, the Leeds General Cemetery remained a place segregated by class and wealth. However, the LGC served an important function in allowing for lower cost, dignified burials regardless of denomination or political belief.

If you would like to read more about how a person’s class, occupation or income affected the location of their grave within the Leeds General Cemetery, then take a look at this report. It is an investigation into the research potential of the data which was generated in the digitisation the cemetery’s burial records.

Report: Statistical Analysis and the Leeds General Cemetery Dataset by Imogen Gerard and Kelsie Root is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.